MORE ALIKE THAN DIFFERENT

by Drema Hall Berkheimer

We are more alike, my friends, than we are unalike.

—Maya Angelou

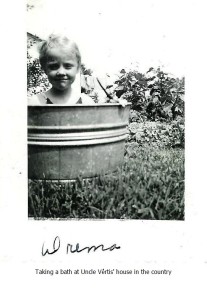

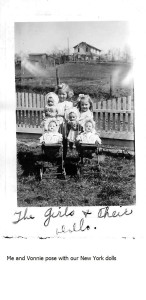

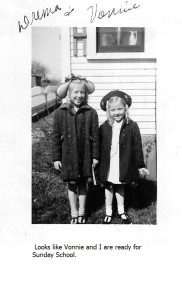

When I was a little girl my Pentecostal grandpa and grandma took care of me while my mother went off to New York to work as a Rosie the Riveter during WWII. They took me to one-room churches they started in little coal mining towns in and around Beckley, West Virginia—that was before I was a Baptist, and before I became the Methodist I’d wanted to be since I was five.

Here’s what I learned on my ecumenical journey.

Every one of us probably has a thing or two in our beliefs that might seem, well, a little peculiar to others.

It does not matter.

We are more alike than we are different.

And the wonderful thing is that different does not need to equate to worse.

Or better.

***

This chapter is excerpted from my memoir, RUNNING ON RED DOG ROAD and Other Perils of an Appalachian Childhood, release in April by Although it’s not as good as being there, I’ve tried to paint a picture of dinner on the ground, a venerated tradition in the South—not only in Pentecostal circles, but in other churches as well. It was a special get-together. I’m sorry you had to miss it.

A GIZZARD ON MY FORK

Sometimes the Pentecostals held a revival meeting in a tent that looked big enough to hold the circus that came to town every year. Ragtag boys from the neighborhood hoped to earn pocket change for setting up rows of mismatched fold-up chairs. A big sign across the makeshift stage declared JESUS SAVES, and the evangelist preaching might be a little bit famous in Pentecostal circles.

Side flaps of the tent were folded up so you could hold to the hope a whiff of breeze would find its way through the crowded rows to where you were sitting. A chorus of preaching and praying and shouting and singing blurred into the night. The hymn “Just as I Am” flowed over bowed heads as the service came to a close.

Moths as big as baby birds flocked around the lights.

We kept the good bedroom, the downstairs one with a small sitting room attached, for visiting missionaries and preachers, the rest of us crowding upstairs into three low-ceilinged attic bedrooms. The little-bit-famous preacher came home with us from the evening service. Grandma heated up the blackberry cobbler and whipped up a whole mixing bowl of fresh cream.

The preacher patted his mouth with a napkin made from a white flour sack.

“Sister Cales, I have been privileged to dine in some of the finest cafes and eateries in Franklin County, and I have not to this day been served anything of an equal to your blackberry cobbler.”

Grandma thought that was worth another helping. The pie, spooned up in flat soup bowls with a generous heap of the cream on top, washed down easy with big glasses of sweet milk.

And that put everyone to sleep in no time.

After the closing service, the Pentecostals held a dinner on the ground. A picnic could be held by anyone, but dinner on the ground was different—only the church held dinner on the ground. Food was pulled from baskets and boxes and paper bags and set out on sawhorse tables made with planks and covered with extra sheets the women had brought. If I squinted my eyes against the sun, the circle of quilts spread on the ground turned into a kaleidoscope of fanciful designs. Folks sitting down to eat their dinners and catch up on the news gradually blotted out the colorful shapes.

“Brother Harvey, you got any Elsie’s pups left? Like to have one for my boy if you do.”

“Sister Sutphin, how’s your girl over in Charleston doing?”

“James Junior, you get your feet off that quilt before I come over there.”

“Be sure to get a piece of Sister Wood’s fried chicken. She soaks it in buttermilk, you know.”

Their voices had the twang of the mountains, like a softly strummed banjo gone a little off tune.

There were whole hams and fried chickens and meatloaves, baked beans and cabbage slaw and deviled eggs, pickled eggs and pickled green beans and homemade sour pickles that turned your mouth inside out before they ever touched your tongue, biscuits and cornbread and loaves of light bread from the store. The men without wives brought the store-bought bread.

“That stuff’s not fit to eat,” Grandma said with a little sniff, but she put a piece on her plate.

Sister Wood’s platter of fried chicken was disappearing fast. Grandma said for me to hurry on over there and get a piece. I sure hoped I could find me a gizzard. Sister Harper saw me poking through the chicken and said, “Honey, I brought them pickled beans you like so much. You go get you some.”

“Yes ma’am,” I said, coming up with a gizzard on my fork.

I wandered over to find me a spot. The Drunkard’s Path was my favorite quilt pattern, but I guess Grandma thought it wasn’t fitting for a church social, so she’d brought a quilt called Jacob’s Ladder. She was busy talking to Sister Wood. I stopped to listen and caught something about that last one being the image of his best friend, but I couldn’t make out the rest. I sidled my way closer.

Grandma gave me a look.

I scooted out of there to get me a piece of cake.

Desserts of all kinds and colors made accidental centerpieces on the tables. There were rhubarb, cherry, and apple crumb pies worthy of blue ribbons.

But Grandma’s cake was best.

She made an Appalachian stack cake with lots of thin molasses-flavored layers put together with homemade cinnamon apple butter. She told me stack cake was used for weddings and funerals when she was a girl. Baking was costly, so each woman brought a layer to add to the cake or a jar of apple butter or cherry preserves to smear between the layers.

Brother Dub called for me to bring him some of Grandma’s cake. His last name was Williams, but everybody always just called him Brother Dub. Grandma said the Dub probably came from the first letter of his last name. He only had one leg so it was kind of hard for him to get around. Grandma said he’d got his leg blown off in the War and that was a shame. I cut an extra big piece and walked it over to him, balancing it on two slightly greasy hands.

By way of thanks he said it looked like I just might grow up to be as fine of a woman as my grandma. I didn’t have the heart to tell him about me and Sissy gambling with real cards all night.

Finally everyone picked up their dishes and quilts and, like a scene played backwards, everything went back into baskets and boxes and paper bags.

It had been a grand day.

A shooting star silvered through the dusky sky. I stopped and closed my eyes to make a wish. I wished for my mother to come home.

Grandma said if I didn’t stop being such a slowpoke we never would get home.

“Yes ma’am,” I said.

***

The War was over and Mother came home. Grandpa died and Grandma moved to Florida. Our lives were forever changed. Yet still, when autumn days crisp and the last leaf falls, I think of tent revivals and dinner on the ground and to a congregation softly singing “Just As I Am.”

The people and places of my Appalachian childhood turn in my head.

And I am running barefoot on a red dog road.

2018obes de cocktail mousseline de soie. Regardons la finesse de mousseline choisie et les détails d’ornement exquis, il n’y a aucun doute que vous tombez amoureuse avec notre robe de cocktail en mousseline de soie.

Drema Hall Berkheimer was born in a coal camp in Penman, West Virginia, the child of a coal miner who was killed in the mines, a Rosie the Riveter mother, and devout Pentecostal grandparents. Her tales of growing up in the company of gypsies, moonshiners, snake handlers, hobos, and faith healers, are published in numerous online and print journals. Excerpts from her memoir, RUNNING ON RED DOG ROAD and Other Perils of an Appalachian Childhood, won First Place Nonfiction in the 2010 West Virginia Writers competition. She is a member of West Virginia Writers, Salon Quatre, and The Writer’s Garret. Berkheimer will be on the panel with Homer Hickam at his Writer’s Workshop in Beckley WV in October. She lives in downtown Dallas with her husband and a neurotic artistic cat. The cat takes after her. Her husband is mostly normal.